China is Using its Currency to Stockpile Copper and Grains

In the TradeSmith Decoder model portfolio, we have a large position in a top-tier copper miner that was up more than 190% as of last Friday’s close. For that we say: “Thank you, China.”

There are other crucial factors driving the price of copper higher — and grains, too — but China is a big one. China has been using its exceptionally strong currency, the yuan, to stockpile copper and grains.

This activity means China is exporting inflation to the world. As China’s relentless demand pushes prices up, food costs and construction costs rise in other countries. A weak U.S. dollar — the flipside of China’s currency strength — is also contributing to global inflationary pressure, as base metals and grains are generally priced in dollars.

China by itself accounts for roughly half of global metal demand. At the same time, China’s grain demand is now breaking records.

China has a sizable corn deficit as a result of livestock needs — it is trying to rebuild its domestic hog supply after a mass-culling due to swine flu — and China wheat imports for 2020-2021 are forecast to be the highest in 25 years.

At the same time, China is ramping up copper demand as its domestic economy rebounds faster than everyone else’s, as a result of dealing with the pandemic earlier on.

“The nation’s factories are charging ahead full steam,” the New York Times reports. At the same time, the NYTadds, “China’s share of world exports rose to a record 14.3% in September.”

Because exports are still moving briskly out the door, China can focus on stockpiling grains and metals with its increasingly hard currency, rather than sweating over non-competitive export pricing.

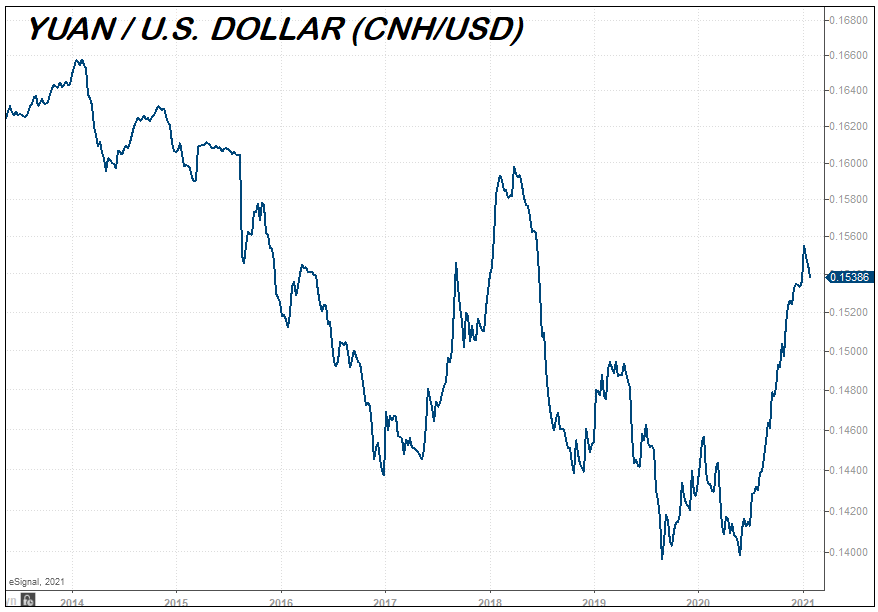

The chart below shows the strength of China’s currency in U.S. dollar terms. It was in the third quarter of 2020, when the yuan had rocketed off a textbook “W” bottom, that China’s stockpiling efforts got aggressive.

Of course, no fiat currency is valued in a vacuum; its quoted price always comes in relation to some other currency (or an alternative benchmark like gold). And as we mentioned earlier, the flipside of a super-strong yuan is a super-weak dollar.

That picture does not look set to change. As we explained in our recent piece on 50 years of U.S. dollar policy, there are plenty of reasons to expect ongoing dollar weakness ahead — not just for months or quarters, but years.

The dollar could have its temporary rebound periods and countertrends here and there, but overall, there is great impetus for it to fall (and then fall some more — and then still more).

For copper and grains, the twin drivers of Chinese demand and U.S. dollar weakness are making a structurally bullish supply-and-demand picture look even more bullish.

Regarding copper, the world is facing the prospect of built-in, long-term supply shortages even as demand ramps up to never-before-seen heights.

As we have said before in these pages — on July 20, 2020, we explained why “Copper is Heralding a Rise in FDR-Style Public Works Projects” — the world is about to embark on a wave of ambitious infrastructure projects in an effort to get past the pandemic slump.

The U.S. is likely to lead the way with a multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure package, but other Western nations, like Germany and the U.K., are likely to follow suit.

At the same time, the “green industrial revolution” now taking place — a process in which electric car-charging stations vie with gas stations, solar panels see exponential uptake, and millions of homes and businesses are retrofitted for energy efficiency — will demand vast amounts of copper.

That is good news for the world’s copper miners, but it is also bad news because they are nowhere near prepared. The mining business is highly cyclical, and the world’s miners come into 2021 with significant cutbacks to their production budgets.

Global mining investment has been depressed for years — it is roughly a third of the levels from five years ago, according to commodities research firm Wood Mackenzie — and is not expected to rise in 2021.

Copper’s last boom peaked out in spring 2011. By the summer of 2016, copper prices had fallen more than 50%.

That level of pain made investors gun-shy of funding new copper projects, and caused management itself to cut back on investment, devoting more capital to paying down debts instead.

What this means is that, if demand sees a sustained surge — due to the aforementioned big industrial projects and green energy rollout — it could take copper producers years to catch up.

And in the meantime, we could see relentless China demand on one side, and an ever-weakening dollar on the other.

With respect to China’s aggressive grain buying, the outlook for global food inflation is further stoked by dwindling grain stockpiles in the United States. A few weeks ago, a monthly supply-and-demand report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) caused grain prices to skyrocket, with corn, wheat, and soybeans hitting their highest levels in seven years or more.

One of the factors there was dry weather in both the U.S. and South America impacting production more than expected: When there isn’t enough rain, the crops don’t grow. Global grain supply was also restricted by government responses to the pandemic, with multiple grain-producing countries restricting their exports.

The truly unsettling question, when it comes to grains, is what happens if we see a continuation of record-busting China demand, a weakening dollar (which boosts commodity prices), and a full-on global drought.

In the North American drought of 1988 — one of the worst drought seasons ever in the United States — soybean prices rose more than 100% in less than a year; wheat prices rose more than 70%. An event like that today could trigger a shutdown of international grain markets, or even provoke a military conflict.

Apart from a long-term bullish copper-and-grain outlook — grain demand should rise globally, alongside copper demand, as emerging market economies strengthen — another takeaway is to be cognizant of inflation risk. There were already plenty of factors pointing toward a return of inflation in 2021. A voracious China appetite for copper and grains, and a U.S. dollar in a multi-year downtrend, will only fan the flames.