What a Smooth Con Man Can Teach Us About Inflation

In 1925, a con man named Victor Lustig was living in Paris.

At the time, local officials were dealing with an ugly and somewhat useless structure built during the World’s Fair in 1889.

The Eiffel Tower was an eyesore that then-resident and famed writer Alexandre Dumas called a “loathsome construction.” The tower’s 20-year permit had expired two decades prior. The tower’s only use was to hold up transmission towers for radios and encourage some tourism.

A lot of people in Paris wanted the tower gone.

So Lustig pounced on the sentiment.

He found Andre Poisson, a new resident in town who operated in the scrap metal business. Lustig convinced Poisson that he worked for the city and needed to remain anonymous. He told Poisson that he was a meager city official with low pay but that he had the power to decide which business would receive a contract to scrap the Eiffel Tower. Poisson bit, paid Lustig $20,000 in cash, and gave him another $50,000 to rig the contract.

And when he realized he’d been conned, Poisson was too embarrassed to report the crime.

Victor Lustig was the man who sold the Eiffel Tower.

And that wasn’t even his most remarkable con.

His most famous con is one that can teach you a lesson about inflation.

What’s In the Box?

The Smithsonian has dubbed “Count” Victor Lustig as the smoothest con man who ever lived.

It’s hard to argue with this title. But what tops selling the Eiffel Tower?

How about a bit of an engineering feat that he accomplished dozens of times?

In the late 1920s, Lustig had perfected a scam in Europe and the United States known as the “Rumanian Box.” It was pretty simple.

Lustig would travel with a large box, about the size of a typical wooden trunk. It was ornate and made out of mahogany. Its outward appearance helped sell the con.

The box had a specific function. Lustig said it could duplicate any currency in the world. It only needed six hours to make an identical copy of the currency. The box had two slots. One to insert money into it, and the other to receive “freshly printed” money from it.

Lustig would ask a fool to hand him a $100 bill. Then he would put the $100 bill into the first slot. Then, after six hours of “chemical processing,” another $100 bill would appear.

Shazam! The box could literally “pay for itself,” as Lustig put it. He would demonstrate this several times.

To the amazement of crowds, his magic money-printing box would create “duplicates.” In reality, Lustig had just packed the trunk full of money to give the illusion that it actually worked and fool the target.

At that point, people would offer him huge sums of money for his magic money box.

He would initially refuse to sell it. But, as with any good illusion, the audience bit harder and harder. Finally, people would offer huge sums for this money box – in the typical range of $20,000 to $30,000 ($310,500 to $450,000 in today’s money). And given that he had secured enough time for the “processing” of multiple bills, he had plenty of time to escape once he sold his box.

In a few noted cases, he would sell the box on a ship before a handful of would-be bidders. Then he’d depart the boat right before it left the port, giving him ample time to escape.

He even tricked a Texas sheriff and a county tax collector out of about $123,000 for the money box in perhaps his most famous encounter with it. Incensed, the Texas sheriff tracked Lustig to Chicago. Lustig successfully talked his way out of trouble by convincing the sheriff that the man had operated the money box incorrectly.

Lustig even handed the sheriff a wad of money for his troubles.

The cash turned out to be fake.

Monetary Problems

What’s interesting about Lustig’s money scams and counterfeiting isn’t how he did it.

It was the impact that he had. His counterfeiting operations were extensive – and he even found himself working to entrust himself to Al Capone.

The Secret Service was worried that Lustig’s massive amount of counterfeit money could disrupt the U.S. monetary system in the 1930s.

That’s pretty rich, especially nearly 90 years later, at a time when the Federal Reserve has been printing money itself out of thin air. The central bank, it seems, has its own magic money box as well.

Last year, the U.S. central bank dramatically increased the U.S. supply of money in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak.

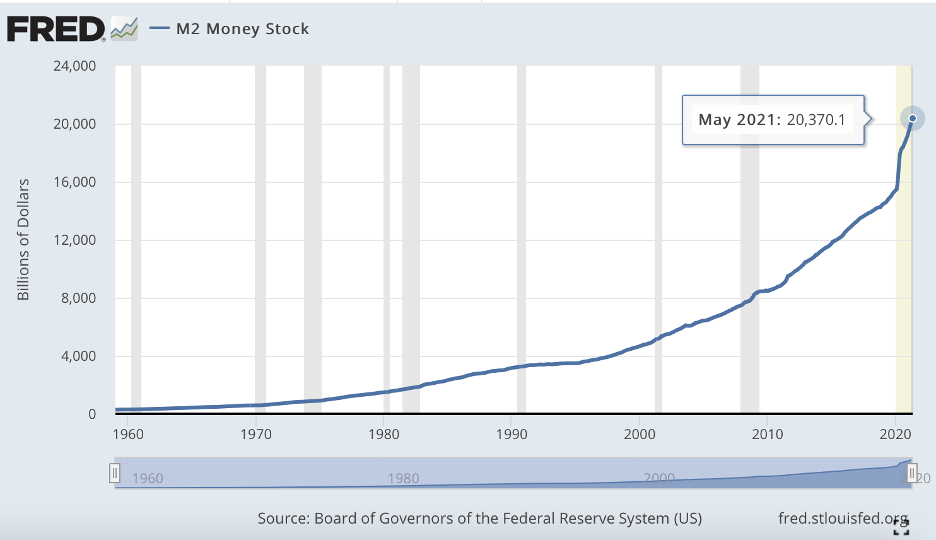

The U.S. M2 money supply increased from $15.4 trillion in February 2020 to $20.3 trillion in May 2021. That’s a 31.8% increase in the U.S. money supply in roughly 15 months.

Not even Lustig could imagine pumping that much money into an economy out of thin air.

But that’s really what the Fed has done with its expansive monetary policy actions. Now that we’re on the other side of this crisis, inflation is kicking in.

So, it shouldn’t be any surprise that printing money and increasing its supply will profoundly impact consumer and producer prices.

Yesterday, the Producer Price Index – broadly a reflection of inflation in U.S. supply chains – increased by its sharpest levels since 2008.

And while the Federal Reserve has said that inflation will likely be “transitory,” economists are not so convinced anymore by this suggestion. As I noted yesterday, the Wall Street Journal surveyed economists across the country. Respondents argued that the U.S. economy would see inflation run above the Fed’s target inflation rate of 2% through 2023.

How to Play Inflation

As I noted yesterday, investors need to think about companies that can pass along any uptick in inflation to their customers. The most obvious is to take the simple approach in real estate. For example, real estate investment trusts (REITs) that operate with “triple-net leases” typically have step-up clauses that protect them against inflation. As a result, these operators can increase rents on their occupants and protect their bottom line and profits from inflationary measures.

I thought a lot about approaching this sector, and the one that made the most sense is the one that generates a lot of cash.

Check out casino REITs. These companies own casino properties across the country and rent these facilities to casino operators. There are three big casino REITs across the United States, and each comes with a strong dividend and reliable upside: Gaming & Leisure Properties (GLPI), MGM Growth Properties (MGP), and VICI Properties (VICI).

The first one, GLPI, is intriguing since it has a diverse portfolio of regional properties across the United States and has a 100% occupancy rate. The latter two operate larger casino properties with a focus on Las Vegas.

Regardless, it’s hard to go wrong if you’re protecting yourself against inflation through a cash-heavy industry with reliable tenants and growth potential. Companies like GLPI and VICI have strong cash flow and are always looking for new properties to purchase and generate new rents for their investors.

All three REITs currently sit in the Green Zone, and MGP and GLPI both exhibit an uptrend in momentum. However, that doesn’t mean that momentum won’t return for VICI Properties. The prospect of inflation might be the perfect catalyst that pulls many investors into these REITs.

Add all three to your watchlist and act on them should momentum bounce back soon.