Fed Chairman Powell to Inflation Hawks: Chill Out For Now

Inflation hawks need to relax, and perhaps even chill out a bit: The Magic 8-Ball forecast for when inflation roars back is still “Reply Hazy, Try Again.”

That was the implied message of Jay Powell, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, in a not-so-subtle pushback this week against rising fears that inflation will quickly become an economic problem.

In no small measure, that is our message, too.

As we have previously laid out in these pages, we certainly believe inflation — real, sustained inflation, of the type not seen for at least a generation — is coming at some point down the road. Signs of inflation’s return are already creeping in at the margins. You can almost sort of smell it, like the smell of rain before a thunderstorm.

But real and sustained inflation, of the type that truly disrupts economic activity, is probably months away; and could even be multiple quarters away; and might yet be a full year or two away.

Before getting to Powell’s remarks — and the nuance of expecting inflation later, but not sooner — we should touch on the topic of market timing.

In trading and investing, timing matters a great deal. That is because being too early, or too late, can have the same de facto impact as being wrong in terms of portfolio profit and loss.

Being too early on an investment theme, or an acted-upon market expectation, can mean getting discouraged and exiting with a loss before the actual move plays out; whereas being too late can mean only getting table scraps, or worse yet, missing the meal while receiving the bill.

What’s more, timing is often assumed to be a trader’s concern more-so than a patient investor’s concern. But that is not accurate, as patience only goes so far. The timing factor matters, even when it comes to longer-term trends and big picture investment themes — it just plays out on a larger scale.

To put it another way, timing matters for the long-term investor not with respect to incremental price changes, but the anticipated timing of a major shift in trend.

Consider, for example, the investor who behaves as if systemic inflation will show up in two months, when in reality it might not be due for 20 months.

That investor could allocate their portfolio heavily toward inflation-related investment plays — and then feel disappointed and dispirited when the value of his holdings goes down, rather than up, for months or quarters on end.

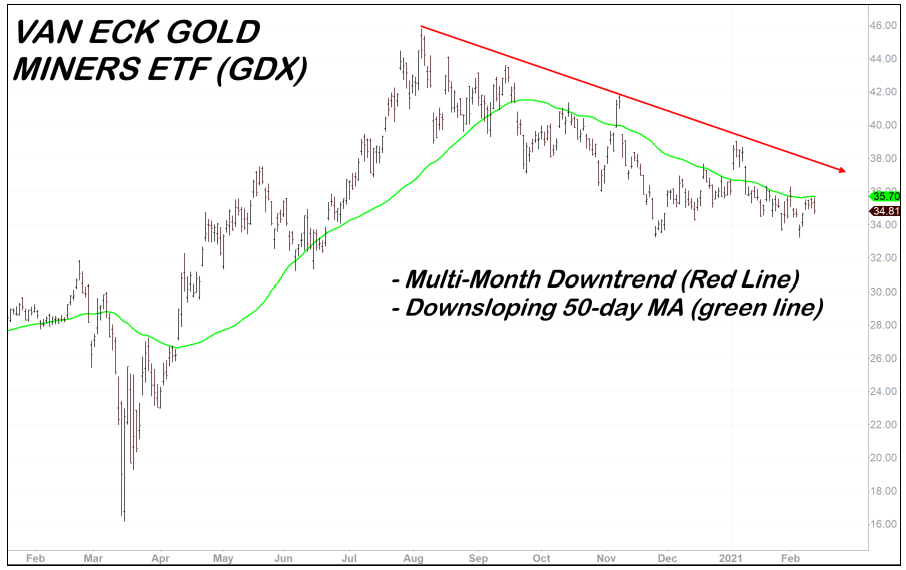

As an example of this, take gold stocks as represented by GDX, the bellwether gold stocks ETF. Gold stocks are in a downtrend right now and have stayed in one for months. We can see this with a glance at the GDX chart.

Gold stocks as a group (as represented by GDX) broadly peaked in August 2020, as did the gold price. Gold-related investments have been in a downtrend ever since, as defined by a series of lower highs and lower lows for GDX, coupled with a down-sloping 50-day moving average (the green line on the chart).

For the investor who is long-term bullish on gold stocks, the question is, when will the broad trend turn up again? Time will tell, and inflation (or a persistent lack thereof) will be a key factor.

Perhaps the back-to-bullish trend turn for GDX will come in three weeks; or perhaps it could be three months; or perhaps it could be 30 months.

That window of possibility as to when the trend could turn up again — from three weeks to 30 months, to roughly illustrate an order of magnitude — is far too wide for our taste.

Some investors will say: “We like gold stocks; we don’t mind waiting.”

We prefer to say: “You know what? We’ll check back in with gold stocks when the trend actually turns. Whether that happens in April 2021 — or, say, December 2022 — we’ll deploy capital elsewhere in the meantime.”

Timing! For way too many economic pundits and market commentators, timing doesn’t matter, because they aren’t putting real money to work.

But as the GDX chart demonstrates, for those who actually trade and invest in pursuit of profits, timing is a big deal, because a capital deployment effort misjudged by months, quarters, or even (gulp) years can be a very costly thing.

Getting back around to inflation — and soon enough to Powell — we anticipate inflation’s return, but not necessarily right away. It will probably take time for various inflation pressures to build up, and there will be moderating forces that push back against it.

Take the lingering impacts of the pandemic, for example.

- The lower half of the U.S. economy, and the small business landscape overall, has been devastated by COVID. Trillions of dollars in new fiscal stimulus — complete with “helicopter drops” of direct payment — will help overcome that devastation, and likely produce inflation as a longer-term result.

- But in the meantime, lingering economic pain could act as a moderating force that pushes back against inflation pressures, even as stimulated recovery efforts generate real economic growth.

- Fiscal stimulus is an inflationary force aimed at overcoming COVID-related pain; but the OVID-related pain will itself absorb some of the inflationary pressure, allowing for growth without inflation early on (and the inflation bill coming due later).

Or consider the impact of rising yields at the long end of the U.S. Treasury curve:

- A sustained rise in the 10-year and 30-year U.S. treasury yield is seen as ominous for the government debt burden, because the higher yields go, the higher the debt-service cost becomes (as expressed by interest payments on the national debt).

- But rising yields at the long end of the curve, coupled with short-term rates near zero, are a very bullish development for banks, as the banks make money by borrowing at short-term rates and lending at long-term rates. The steeper the yield curve gets — a measure of short-term rates versus long-term rates — the more profits that accrue to the banking system, making banks more eager to lend.

- Trillions in fiscal stimulus will add to the debt burden, but it will also spur real economic growth in at least two ways: Money that goes into the pockets of consumers and small businesses will be immediately spent; and banks will have increasing willingness to lend in the midst of a real recovery.

To put that more simply: If growth comes first, and inflation comes later, then the smart move is to invest in growth-oriented areas of the market, rather than inflation-oriented areas of the market.

Real economic growth is good for “reflation plays” related to areas of the market like industrials and consumer goods; it is not so great for inflation havens like precious metals. Inflation is just the opposite — it is good for inflation havens like precious metals, but not so good for growth-oriented reflation plays.

Getting that mix right — anticipating the mix of real economic growth versus inflation, when coming out of a recession and a pandemic, with a cartoonishly expanded money supply and trillions of dollars in fiscal stimulus at work — is a very tricky thing.

It is such a tricky thing, in fact, that we would rather defer to the market’s opinion (as expressed through charts and price action) than be overly confident in our own assumptions.

On that score, were inflation a truly imminent concern, the gold price would be trending higher (it has been trending lower for months); the 10-year U.S. Treasury note would have a yield above 2% (instead it is modestly above 1%); and inflation-vulnerable areas of the stock market, like utilities, would be experiencing price dislocations and downtrends (they are not).

So why are inflation hawks getting flustered too early? In our view — or rather, our interpretation of the market’s view — they are missing the concept of “growth first, inflation later” and putting the cart before the horse.

The horse is named “growth and recovery,” the cart is named “inflationary consequences”, and the horse is supposed to come first, dragging the cart along behind it, with the contents of the cart to be unloaded at a future time.

Areas of the market that could forecast either real economic growth or signs of inflation, depending on one’s interpretation — we speak here of the oil price and copper price, to give two examples — thus deserve the growth interpretation, in our view, rather than the inflation interpretation, because adjacent areas of the market that express pure inflation concerns (e.g. precious metals) are not at all doing well.

As such, we interpret price signals like Brent crude above $60 per barrel, and the copper price trading at nine-year highs, as the market’s anticipation of real economic growth — because that is what the market itself is saying, by way of the current price mix.

And that mix is wholly commensurate with, drumroll please, a stimulus-driven economic recovery that presents growth now, and a nasty inflation bill later — with the timing on “later” being measurable in months, or quarters, or possibly even a year or two.

Timing again! This isn’t just a fun puzzle for those who enjoy the intellectual aspects of putting the pieces together; it is also a puzzle that can make an investor rich, if they can determine the proper sequence of actions (deploying capital not just to the right mix of places, but also at the right time).

Our willingness to defer to market judgment as expressed through price signals makes it easy to agree with Jay Powell, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, in his not-so-subtle suggestion this week that newly minted inflationists are jumping the gun.

Chairman Powell’s “stop fretting over inflation” message was delivered on Feb. 10 in a speech to the Economic Club of New York.

Here is the part where inflation concerns were dismissed:

“You could see strong spending growth, and there could be some overt pressure on prices. My expectation would be that will be neither large nor sustained. Inflation dynamics will evolve but it’s hard to make the case why they would evolve very suddenly in this current situation.”

Translation: An economic recovery will drive spending growth, which in turn could push prices up — but that isn’t the same as sustained inflation, which will take a while to get going, so don’t sweat inflation for now.

In the same speech, Powell emphasized the importance of helping out the labor economy, which means taking aggressive action to get struggling Americans and small businesses back on their feet:

“A strong labor market that is sustained for an extended period can deliver substantial economic and social benefits, including higher employment and income levels, improved and expanded job opportunities, narrower economic disparities, and healing of the entrenched damage inflicted by past recessions on individuals’ economic and personal well-being.

At present, we are a long way from such a labor market. Fully realizing the benefits of a strong labor market will take continued support from both near-term policy and longer-run investments…”

Translation: We’ll all be better off when recovery benefits are widespread, and a stronger labor market will mean a stronger economy on the whole.

The second part, about helping the labor market, is also a “don’t worry about inflation” message because, to the extent policy drives real economic growth, income and yields and prices can rise without inflation becoming a problem.

To be sure, we think the Federal Reserve and Treasury will lose control of the inflation narrative at some point.

The U.S. government’s willingness to help the economy through brute force, via the unleashing trillions of dollars in monetary and fiscal support, will eventually touch off the kind of inflation pressures America hasn’t seen since the 1970s, or even the late 1940s in the aftermath of World War II.

But the key word there is “eventually.” In the near to medium term, market price signals seem to back Powell’s stance: Growth and recovery is the part that comes next, with inflationary consequences postponed.