Last Week’s Market Structure Event Was One of the First Popcorn Kernels to Pop

On Feb. 26 — less than a month ago — we explained why risk levels were elevated for a “Market Structure” related meltdown event. A few weeks on, the danger has only grown.

As we said in the piece:

A market structure event is major price dislocation — like a meltdown or a flash crash — that happens for reasons unrelated to investor sentiment or a long-term fundamental outlook.

Market structure is a reference to the way investors are positioned: Who is long, who is short, how much leverage they have, and so on.

The phenomenon of “portfolio contagion” is notably a market structure issue: If leveraged hedge funds take a large hit to a certain area of their portfolios, for example, they often have to liquidate positions in unrelated areas of the portfolio to reduce exposure across the board.

In this manner, a sell-off can be contagious in that the selling jumps from one area of the portfolio to another; the linking factor is the structure of what the hedge funds are holding.

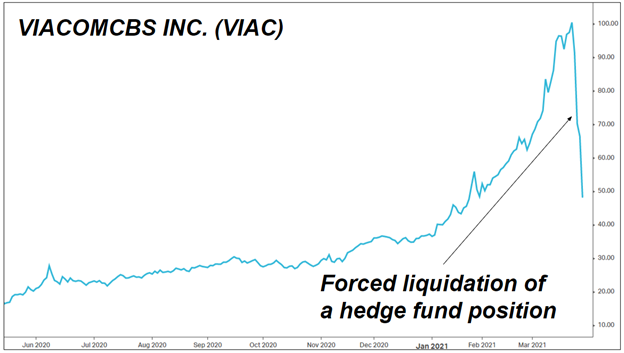

If you are curious what a market structure event looks like, here’s a fresh example. Check out the below chart of ViacomCBS (VIAC), which was one of the year’s best-performing names prior to last week.

Wall Street was shocked on Friday as a single hedge fund, Archegos Capital Management, had more than $20 billion worth of positions liquidated by its brokers as a result of unmet margin calls.

This fund was seriously leveraged, according to sources who spoke with Bloomberg.

Archegos was estimated to have $5 billion to $10 billion worth of assets under management, but anywhere from $4 to $9 worth of leverage for every $1 of capital. That made the fund’s total equity exposure as much as $50 billion against a base of $5 billion to $10 billion.

At four-to-one leverage, a 20% move can wipe you out. And at nine-to-one leverage, a 10% move can wipe you out.

It appears that ViacomCBS (VIAC) and Discovery Inc. (DISCA) — two media stocks that had run up hugely year-to-date — were having a bad week, with selling pressure leading to double-digit declines.

The double-digit declines then triggered a margin call for Archegos, which appears to have been leveraged up to its eyeballs in VIAC, DISCA, and a handful of other names.

When a whale-sized hedge fund goes into forced liquidation, the prime brokers who handle the fund’s accounts will execute “block trades” — the buying or selling of large blocks of stock — to close out the impacted positions as soon as possible, to avoid the danger of the account going negative and leaving the prime broker with losses on its books.

On Friday March 23, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and others executed tens of billions in block trades — Goldman did $6.6 billion alone prior to the market open — to liquidate the fund’s holdings.

The forced liquidation led to valuation wipe-outs significantly in excess of the block trade size. On Friday alone, an estimated $35 billion worth of market cap evaporated, mostly concentrated in Chinese technology companies and media conglomerate stocks.

Market structure events are typically not one-off occurrences. They are more like a bag of popcorn in the microwave. First you hear a single, solitary pop. Then you hear another… and then another on a shorter time delay… until finally a crescendo as hundreds of kernels pop at once.

The reason this happens is because, particularly at the tail end of a bull market period, hedge funds tend to be jam-packed into the same types of positions.

At the same time, leverage levels tend to be their highest at a market peak, and the overall leverage ratio for U.S.-based long-short hedge funds was recently still above 200%, according to Morgan Stanley data.

So, what happens is, you have a significant number of market players who are “long and wrong” in the same names at the same time — and they are not just wrong in a modest way, they are wrong while significantly leveraged.

As a result of this crowded positioning, a correction-level decline (10% or more) in a popular industry group can wind up triggering a margin call for a particular large fund — and the pain of the forced liquidation that ensues transmits losses to other portfolios with the same or comparable exposures.

And if market forces were already conspiring against the overextended, overvalued group of stocks these funds were long — like, say, rising 10-year and 30-year yields putting direct pressure on wildly overvalued technology stocks, even as China’s stock market melts down (it is already happening there) and a rising tide of new supply in the form of SPAC issuance and IPOs continues to flood the market — that tends to make the selling pressure worse, as a critical mass of funds ponder heading for the exits before their own margin calls hit.

The market danger here remains severe — for technology stocks in particular, if not the market overall.

In our view, last week’s forced selling in names like VIAC and DISCA marked the start of a rolling liquidation phase — one of the earliest kernels in the bag of popcorn to pop — and we might now be entering a period like the ones that followed March 2000 and March 2007, where the real pain was just getting started.