The Man Who Broke The Back of Inflation

Interest rates in the United States have been falling for nearly four decades. That was largely due to one man, Paul Volcker, who died this week at age 92.

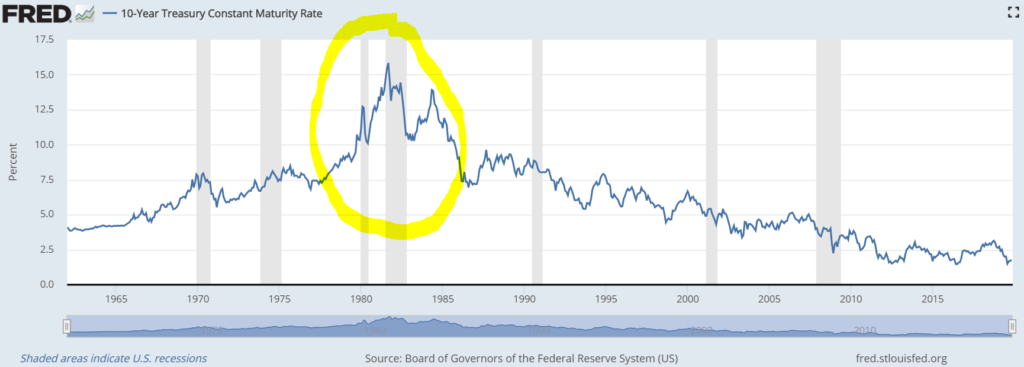

The 10-year U.S. treasury yield, according to the St. Louis Fed, peaked in the vicinity of 16% in September 1981. As of this writing, the 10-year yield is below 2%.

From a starting point of 16% to sub-2%, that is one heck of a slide. Some believe it will fall lower still, and that sub-1% is in the cards.

Falling long-term interest rates are largely a byproduct of stable or falling inflation. We live in a low-inflation world, and the United States has enjoyed stable-to-falling inflation for decades.

This reality was made possible by Volcker, who served as Chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1987. Thanks to his aggressive inflation fighting efforts, Volcker earned the nickname “the man who broke the back of inflation.”

Before he was made Fed Chairman, inflation raged all throughout the 1970s. Inflation expectations were built into everything. Unions were constantly negotiating for higher wages, on the assumption that six months down the road, their paychecks would be worth less.

Consumers and banks were also playing the game. The idea was that, if you wanted a toaster oven or some other consumable good, you might as well buy it now, because in six months, the price will be more expensive. Banks played the game, too, encouraging consumers to buy on credit.

The stock market hated all this. When Businessweek ran its famous “Death of Equities” magazine cover in August 1979, inflation was blamed for eating corporate profits like termites in the foundation of a house.

In his finance career in and out of government, Volcker had watched as prior central bank chiefs got bullied. Presidents Nixon and Johnson both wanted “easy money” policies to help their campaigns.

When he took the reins in 1979, Volcker was determined to stop inflation no matter what it took. That meant a willingness to endure pain — lots of pain.

As Fed Chairman, Paul Volcker tied interest rate policy to the money supply. This meant interest rates would rise until the money supply fell to a desired level.

And boy did interest rates rise. Under Volcker, interest rates went up and up until people screamed bloody murder. This sent the economy into a brutal recession, which was necessary, Volcker argued, to slay the dragon of inflation.

Volcker is recognized as a hero because he was willing to be intensely disliked, or even hated, for the sake of doing the right thing. In the worst part of the recession, out-of-work homebuilders were so angry they sent stacks of two by fours to Volcker’s office. Politicians in Congress raged that Volcker should be fired, and he received so many death threats, he was ultimately given Secret Service protection.

At the end of the day, the rate hikes worked. The key was breaking the psychology of inflation expectations, which required a man like Volcker who was so principled and so stubborn the country had to realize he would never back down.

Volcker’s contribution to history is literally visualized in the form of a long-term interest rate chart. You can see it in the path of interest rates, as shown below via the St. Louis Fed. The area circled in yellow roughly covers Volcker’s time as chairman.

With Volcker’s death this week, the world has lost a giant of a man. And by “giant” we mean it literally — Volcker stood at 6 feet, 7 inches tall.

Volcker was a true public servant in a style that is rarely seen anymore. As Fed Chairman, he took a hefty pay cut from his private banking career, stayed focused on doing what was right, and was frugal in every sense of the word.

Volcker preferred to fly coach on the frequent plane trips between Washington and New York, which, for a guy who was 6-foot-7, must have been quite a sight. Instead of hobnobbing socially, he liked to roll up his sleeves and work. His only known vice was inexpensive cigars, which probably smelled foul because they were also cheap.

It seems oddly fitting that Paul Volcker, the greatest central banker who ever lived, would pass away near the tail end of a four-decade era he helped create.

If not for Volcker, “the man who broke the back of inflation,” we have no idea how America’s 1970s inflation problem would have been solved.

It remains a huge open question what America will do when high inflation returns after such a long time away — as it will, eventually, because that is the cyclical nature of things. Who will be the new Volcker?

And would a new Paul Volcker even have the stomach or permission to raise interest rates aggressively, given how dangerously leveraged the United States has become?

Rest In Peace, Mr. Volcker. It’s going to be an interesting decade.

TradeSmith Research Team