The US Dollar Will Rip and Run in 2021

In 2020, arguably the single best asset to own in size was Bitcoin. For the coming year, that could easily hold true once again, with BTC having a reasonable shot at it before the year is out.

Apart from Bitcoin — which is practically its own asset class — one of the assets we are most bullish on is the U.S. dollar as a currency, relative to all other fiat currencies. The U.S. dollar looks set to romp and stomp on its fiat counterparts this year.

In the TradeSmith Decoder portfolio, we turned aggressively bullish on the dollar a few weeks ago, establishing sizable positions in various forex pairs, for reasons we’ve covered in these pages (primarily the Quantum Deficit Effect).

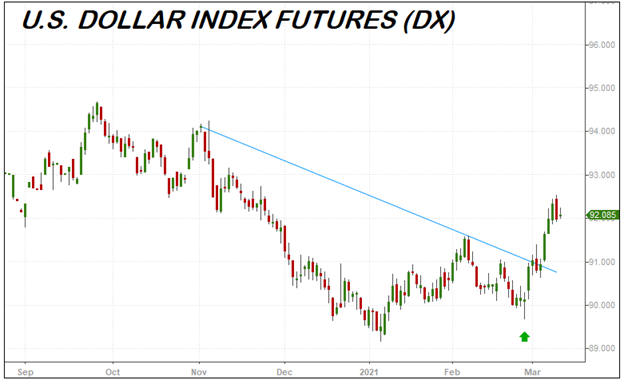

This call was well-timed as shown by the price action in U.S. dollar index futures, which registered a near-term bottom on Feb. 25 and surged higher.

An early surge in the dollar could just be the beginning.

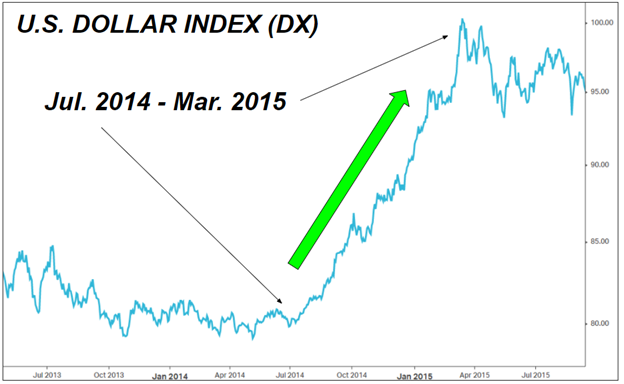

If our read on the situation is correct, the dollar could be in for a quasi-repeat of its 2014-2015 experience, when the world’s reserve currency rose explosively for months on end (as shown in the chart below).

The natural question, then, is what happened to make the dollar rise so ferociously back then — and what are the comparable factors that could create an encore performance in 2021?

In 2013, the bond market had its historic “taper tantrum” — a surprise spike in long-end yields triggered by fears of a shift in Federal Reserve policy.

For years on end, the Federal Reserve had been purchasing large quantities of treasury bonds in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. By 2013, the Fed had started thinking it was time to cut back, at least a little, in a transition back toward normalcy.

And so, in a congressional appearance on May 22, 2013, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said the following in a question-and-answer session:

“If we see continued improvement and we have confidence that that’s going to be sustained, then we could in the next few meetings, take a step down in our pace of purchases.”

Bernanke thought he was suggesting a mild course of action, just easing things back a bit. Wall Street famously responded with its “tantrum,” causing bond markets to plummet and yields to spike.

What the Federal Reserve did in 2013, by accident, was meaningfully tighten monetary conditions. They didn’t do it on purpose; Wall Street overreacted and did it for them.

By the way, Wall Street overreacting to the Fed — and running wildly in one direction or another — happens more often than people think. In the past we have compared the Chairman of the Fed to a jockey riding an elephant. Under normal circumstances the jockey appears to have control, but it’s mostly a psychology trick. If the elephant decides to panic, forget it.

So, the Federal Reserve tightened monetary conditions substantially in 2013 — not just locally, but globally — through a careless choice of words that triggered a “taper tantrum” and a spike in yields.

The global monetary tightness created by a spike in U.S. long-end yields led to weakness in various economies, while making the U.S. economy look stronger by comparison. This created a snowball effect: As more capital started pouring into the U.S. economy, the dollar got stronger, which attracted more capital still, making the whole thing a runaway train.

A comparable scenario looks to be happening again, but for slightly different reasons.

This isn’t just our view, but also that of Robin Brooks, the chief economist for the Institute of International Finance (IIF) and the former chief forex strategist for Goldman Sachs.

“We’re back to a strong dollar world,” says Brooks. “After the global financial crisis, it took four years (from 2009 to 2013) before we got dollar strength. Now it’s only taken a few months. So this recovery is like post-GFC, except it’s on ‘speed.’ Much more stimulus, much faster USD recovery.”

There are a handful of factors here that stand out:

- The expected U.S. growth rate is being revised sharply higher, even as the growth rate for most other countries is being revised downward.

- The sharp rise in long-end yields is a form of monetary tightening, which the Federal Reserve and Treasury are fine with — even as it creates tight monetary conditions in the rest of the world.

- Hedge funds and speculators have larger net-short USD positions in dollar index futures than at any point in the past decade — which makes them ripe for a GameStop-style short squeeze.

One of the reasons the U.S. growth rate is going to be wild in 2021 is because the United States, as the richest country in the world, can afford to splurge on bunker-busting stimulus.

No other country can “buy growth” the way the United States can — they simply don’t have the balance sheet to get away with it, at least in the short-term.

And buying growth is exactly what the U.S. is going to do: We are going to see hundreds of billions in stimulus go directly to Americans whose incomes are below the cost-of-living level.

Those Americans are in turn going to immediately pay rent and otherwise buy “stuff” — diapers, peanut butter, new tires, a new refrigerator, you name it — in a way that will add directly to consumer spending and thus to nominal GDP.

With U.S. growth set to blow past rivals like they are standing still — the outlook for Europe is surprisingly gloomy, due to a badly botched vaccine rollout — there will be plenty of scope for long-end yields to rise further, as investors rotate out of bonds and into financials, energy, transports, and the like.

And as long-end yields in the U.S. bond market rise further, other economies will feel the squeeze of tighter credit conditions through global transmission effects.

Those countries not growing as fast — or possibly not growing much at all — will be forced to proactively weaken their currencies, or otherwise loosen local monetary conditions, to keep their own recoveries from being suffocated.

Then, too, as long-end yields rise for U.S. treasuries, and the U.S. dollar strengthening trend becomes readily apparent, sovereign debt holders in Europe and Japan will be strongly tempted to swap out their lower-yielding European bonds and Japanese Government Bonds in favor of higher-yielding U.S. treasuries.

For those entities that have to hold sovereign debt as part of their charter, going to treasuries will be a double win: If they have to hold sovereign debt anyway, they might as well get the benefit of a higher yield (the U.S. 10-year or 30-year) and a strengthening currency (the U.S. dollar) at the same time.

What we are describing here is a self-reinforcing feedback loop. Blistering growth in the United States powers higher long-end yields; the higher long-end yields create tighter credit conditions for other countries, forcing them to weaken their currencies against the dollar; and a desire to own U.S. treasuries (because of their higher yields) will cause more capital to flow into an already-rising dollar.

As a further benefit to the feedback loop, the willingness of sovereign debt holders to buy U.S. treasuries at superior yields to their home market bonds could keep the bond market from falling too far and too fast.

That, in turn, will let the Federal Reserve and Treasury stay somewhat relaxed, knowing there is a buffer in place (global yield seekers) that will keep yields from rising to too-painful levels via their stepped-up treasury purchases as the U.S. dollar strengthens.

And then, as icing on the cake, futures data via the Commitments of Traders report, updated regularly by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), shows that net-speculative positions in dollar-index futures are at their most bearish levels in more than a decade.

It was an easy thing to be short the U.S. dollar on the assumption that trillions in fiscal stimulus meant a lower relative value for the greenback — but this assumption gets the structural mechanics backwards when the most important factors are added in: Dynamic U.S. growth feeding a rise in long-term yields.

There is even a credible argument that rising long-term yields could help growth accelerate further, to the extent that, against a booming growth backdrop, higher interest rates will incentivize banks to lend cash to small and medium-sized businesses that can actually grow quickly — as opposed to, say, facilitating yet another megacorp loan at an artificially low rate.

If any of this makes it sound like the $1.9 trillion stimulus is a free lunch, it most certainly is not. It just happens to be a lunch (or maybe an epic feast) where the bill comes in delayed installments, in the form of persistent inflation that erodes the value of dollar-denominated debt (thus transferring wealth away from the creditor class, and toward the debtor class, as a matter of de facto policy).

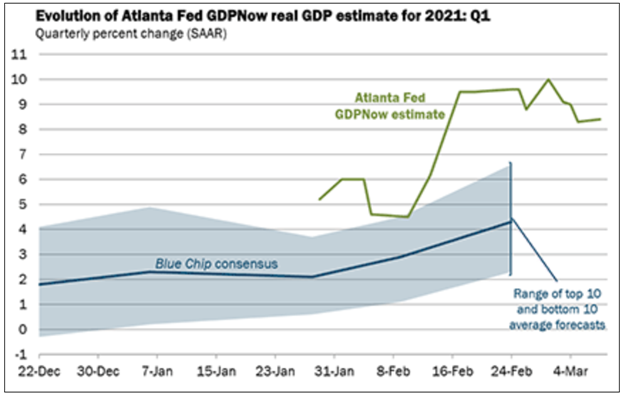

Here and now, though, U.S. growth will begin to roar like clockwork when consumer spending ramps up — indeed it is roaring already, as evidenced by recent “nowcast” numbers from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

The Atlanta Fed’s “GDPNow” methodology looks at economic data series in real time — crunching numbers as they come in — to create a rolling forward forecast for U.S. growth.

As of their March 8, forecast, the GDPNow expectation is 8.4% — a growth rate not seen in 60 years or more! — and that is based on data before the stimulus hits bank accounts.

Barring some wild surprise twist, the outlook is clear. The U.S. economy is going to roar, leaving global counterparts in the dust; long-end yields are going to rise further, creating tighter monetary conditions around the world; and the U.S. dollar is going to roar, too.