Was the Rebound Powered by Sports Gamblers and Stimulus Checks?

The strength of the stock market rebound has been a mystery. (To give you a sneak preview, today we’ll explore a narrative that solves the mystery.)

It’s not just that stocks — not all stocks, but a favored group — are showing a kind of bizarre optimism, relative to a catastrophic collapse in the real economy, the ongoing challenges of the pandemic (with a “second wave” on deck), and the inescapable realities of a painful and prolonged recovery.

In addition to all that, the mystery resides in the divergence. Other parts of the market are confirming reality with nothing lost in translation.

The bond market, for example, is forecasting a very dark picture, both near-term and longer-term. We can see this via near-zero rates at the short end of the curve — the two-year yield is at 17 basis points as of this writing — and a Fed Funds forward curve that still anticipates negative rates by summer 2021.

Experienced investors have also sounded the alarm, adding to the divergence.

Stan Druckenmiller is one of the greatest money managers of all time, having delivered 30% compound returns on billions in assets under management over a 30-year time period — with no losing years. (Just think about that for a second.)

Druckenmiller has said equities at current levels represent the worst reward-to-risk he has ever seen in his career. But the market doesn’t care. Why?

Or take David Tepper, another legend whose face would be on the Mount Rushmore of hedge fund managers, if anyone ever carved such a thing. Tepper, who is known for bullish bets, not bearish ones, recently described markets as the second most overvalued he’s ever seen. But the market doesn’t care.

Or consider Warren Buffett, the greatest value investor of all time. Buffett is also gloomy, as we recently noted. We would argue this is not because Buffett is tired, but rather because he is honest.

For instance, whereas retail investors are willing to buy airlines on the theory that “they went down a lot, so they have to go up,” Buffett understands what is actually in store, which is why he dumped them.

So, the bond market is aggressively bearish. And some of the smartest investors of their generation — all of them huge money-makers, all perfectly comfortable being bullish for years at a stretch, no perma-bears in the bunch — are either gloomy or flat-out bearish. And yet the market doesn’t care.

Maybe it’s the unprecedented stimulus from the Federal Reserve? That’s probably getting closer to the mark. And yet Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve Chairman himself, came out and begged Congress for more trillions, warning outright of the dark road ahead if enough is not done.

We thought it might be down to long-only money managers making a one-sided bet, calculating that there was greater career risk in not being long, and the market roaring up without them, as it did in January 2019, than in being “long and wrong.”

So perhaps the long-only money management community drank the “V-shaped recovery” kool-aid out of self-interest?

Maybe, and yet the Bank of America money manager survey for May 2020 showed that 68% of money managers — more than two-thirds — believe we are currently in a bear market rally, and only 10% anticipate a V-shaped recovery, which they believe would also require a vaccine to catalyze.

If not from the money managers, where is all this optimism coming from?

Never fear, because a theory is here.

In recent days, a narrative has crystallized with a solid amount of evidence to back it. We’ll present it as a series of “What ifs:”

- What if the rally was powered by a bunch of sports gamblers, feeling an urge to bet on stocks in the absence of sports, and a deluge of stuck-at-home millennials punting their $1,200 stimulus checks on their favorite stock market names?

- What if the absence of sports, along with a shutdown of clubs and bars and most all other entertainment activities, caused a great mass of bored individuals to say “welp, I guess I’ll look at the stock market?”

- What if the 2019 pivot to zero-commission-brokerage came just in time for the boredom of the pandemic, with hundreds of thousands of accounts opening up to take advantage of zero commission trading?

- And what if, for the cross-section of Americans who are able to work from home (about 30% of them) and also had an income low enough to qualify for stimulus, the general reaction was, “Hey, why not throw it at the stock market?”

This would explain a lot, particularly why stock market behavior has felt so divergent from reality.

If a market novice — or a bored sports gambler — throws money from the government into the market on a whim, it seems doubtful they would look at valuations, balance sheets, or economic conditions. Instead they would just pick names they like, or things that have gone down a lot, because, why not?

Now let it be said, this theory is pretty wild. It has a lot of moving parts, many of them strange.

As a short list, for the theory to work, you need a bunch of sports gamblers moving into stocks en masse; a huge number of new free trading accounts popping up with the major brokerages; evidence that young people with jobs (those working from home, but qualifying for stimulus) were putting those stimulus checks into the market; and evidence that general public interest in stocks rose intensely during the shelter-in-place period (which would suggest a boredom motive).

All of that evidence exists. Here are some nuggets:

- Charles Schwab, E*TRADE, and Interactive Brokers, the big three zero-commission brokerage houses, added an incredible 780,000 new customers in March and April 2020 — the primary months for lost activities and shutdown boredom.

- Robinhood, the free trading app targeted at millennials, reported that trading activity in March 2020 was triple that of March 2019, and that 72% of all trades were “buy” orders.

- Dave Portnoy, the founder of the sports-betting website Barstool Sports, who got rich selling a third of his company to Penn National Gaming, has drawn an audience of millions via Twitter and Instagram to his head-first dive into the stock market, powered by $3 million poured into an E*TRADE account. Why did Portnoy do this? With sports on hiatus, stocks are a substitute.

Then, too, the stimulus checks were “free money” for those who qualified but didn’t need the dough.

“The U.S. government passed the largest piece of stimulus legislation in our nation’s history to allow people to keep paying their bills during the forced economic shutdowns due to the coronavirus,” CNBC reports. “Consumers, in turn, used a lot of that money to speculate in the stock market.”

According to Envestnet Yodlee, a market-related data aggregator, “securities trading was among the most common uses for government stimulus checks in nearly every income bracket,” CNBC adds. “For many consumers, trading was the second or third most common use for the funds.”

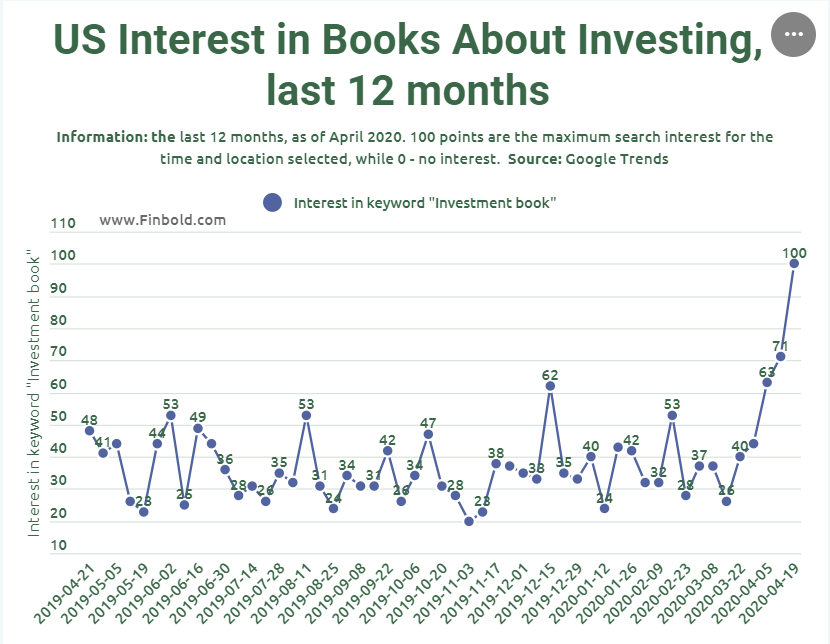

Last but not least, there is the following chart via Finbold.com, which speaks for itself.

There you go. Sports gamblers getting their gamble on, millennials who don’t need the cash buying their favorite names, and consumers in general converting a big chunk of the emergency stimulus directly into equity bets.

If this narrative is true, it is also quite bearish, for the following reasons:

- If this rally was, in a sense, literally powered by boredom, it confirms the hypothesis that optimistic stock valuations are not discounting the carnage of the real economy crisis at all.

- If the rally was heavily powered by stimulus checks — a limited-time distribution — then buying fuel will run out when the stimulus checks stop.

- If optimism is being driven by the 30% of Americans who work from home, cross-sectioned with those whose income level was such that they qualified for stimulus checks but didn’t actually need it, that optimism could fade as the next wave of knowledge worker job losses starts to hit (as real economy crisis conditions trickle upward, causing knowledge worker layoffs, via reduced revenues and sales).

- If a significant amount of market activity was actually driven by boredom, then the prospect of re-opening will remove some of that interest, even as the stimulus check tailwind begins to fade.

- If the pain of the real economy crisis shows up in economic data and earnings reports on a delayed basis — pushed back by the initial rounds of stimulus, rent forbearance, and so on — the cold water of economic reality will be poured on the market even as the sugar rush wears off.

- If the reality of the pandemic and ongoing harsh recovery conditions have not yet been priced in because of the above dynamic, then it could really hurt when that repricing occurs.

We aren’t pro-gloom — and in fact, we have done quite well on the long side all through this rally via TradeSmith Decoder — we are just anti-nonsense. This is because nonsense rallies are dangerous, not just for the stock market, but for the health of the economy on the whole.

Rallies that go too far without logical justification — powered by hope and hype and ill-thought stimulus — can ultimately result in more pain, and more economic carnage, for everyone involved, even those who didn’t bother to participate in the stock market at all, or who didn’t realize they were exposed.

Although asset bubbles can be fun while they last, the violent bursting of an asset bubble is inherently deflationary. The problem is not the party itself, but the killer hangover that results afterwards.

That is why Stan Druckenmiller has repeatedly said that if the Federal Reserve actually wanted to create serious deflation — a catastrophic thing to want — one of the best ways to do it would be to first pump up a huge asset bubble that then bursts, because deflation would come in the bursting as reality hits hard.

Unfortunately, if the narrative of bored sports gamblers and stimulus check punters is correct, it increases the odds that we are heading for a painful readjustment to reality — the reality that the bond market and many others already see — and an ugly market implosion that could well be deflationary.