When a Bounce is Not a “V” (2020 versus 2009 and 1982)

On July 2, the June 2020 U.S. jobs report was released. Nonfarm payrolls jumped by 4.8 million, the largest monthly gain in U.S. history, when a gain of only 2.9 million jobs was expected.

The outsized beat of economists’ expectations was seen as bullish for stocks, at least initially. A larger than expected decline in the unemployment rate, to 11.1%, was also seen as bullish.

But there is a problem here, and it has to do with starting points.

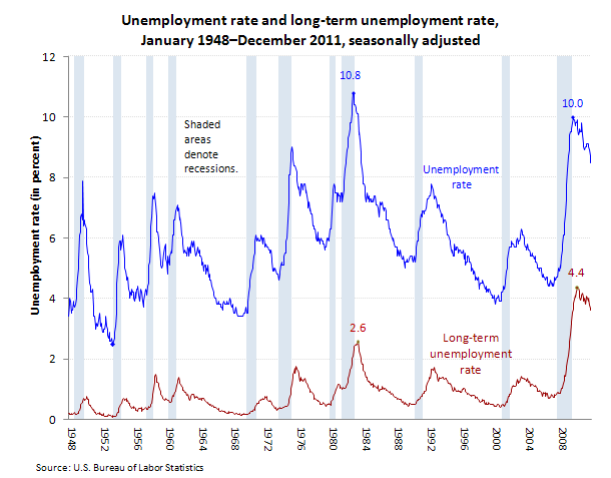

You can see it in the following chart, compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2012:

Do you see the trouble? It has to do with historic peaks in the unemployment rate.

- In 2009, at the worst point of the Great Recession, the unemployment rate at its highest point was 10%.

- In the early 1980s, following a brutal recession caused by sky-high interest rates, the unemployment rate at its highest point was 10.8%.

Meanwhile, in 2020, at a point where the worst may not have passed, the unemployment rate “declined” to 11.8% — a level which, 2020 aside, would be the highest in modern history.

Then, too, the drop seems both fuzzy — the actual unemployment rate could be multiple percentage points higher, as with the month prior — and temporary, as economic optimism around “reopening” in the month of June is being rolled back.

But, again, the real issue here is starting points. A big jump or a big turnaround can be rightfully impressive. But it’s a different thing when starting from the bottom of a very deep hole.

Consider the case of a stock price that triples. In most circumstances, a triple in the share price would be seen as a hugely bullish event. When might it not be?

Well, say that the stock was trading at $40 per share, then fell to 20 cents after a huge accounting scandal, and then tripled from 20 cents to 60 cents as a result of short covering and speculative Robinhood buying.

That bounce, from 20 cents to 60 cents, would be a legitimate triple (a 200% gain). But would it count as bullish in the big scheme of things? Hardly.

What matters in this scenario is how far the share price fell, how deep a hole the company is in, and the risk of the share price going right back to 20 cents (or lower).

We are seeing this dynamic — in which the short-term bounce looks impressive, but the total numbers fell off a cliff — in multiple areas of the jobs report.

“Employment in clothing stores up 202K!” tweeted Betsey Stevenson, a former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Labor. “But it’s still down 40% compared to last year,” her tweet continued. “Many of those jobs are never coming back.”

Comparably, for the U.S. economy, it would be wonderful if a fall in unemployment to 11.8% meant the rapid return of normalcy. But it almost certainly doesn’t, because too many of the jobs still absent are, as Stevenson put it, “never coming back.”

Then, too, if unemployment stabilizes at current levels, it would do so at the worst levels of the modern era, breaking all previous records.

Truth be told, we are still so far from economic “normal” that, in regard to the economy, the word “normal” doesn’t really apply anymore.

The goal now is to win the war with the virus — as of the July 4 weekend, America was losing — and get the U.S. economy back to an acceptable state. Whatever that state turns out to be, it won’t look like the economy that came before.

Consider what Brian Chesky, the co-founder and CEO of home-sharing juggernaut Airbnb, said about consumer travel habits in an interview with CNBC.

“Travel as we knew it is over,” Chesky said. “It doesn’t mean travel is over, just the travel we knew is over… we spent 12 years building Airbnb business and lost almost all of it in a matter of four to six weeks.”

“I think that travel is going to come back,” Chesky added. “It’s just going to take a lot longer… and it’s going to be different.”

That sounds about right. There are old patterns of behavior that will be disrupted permanently, or otherwise completely gone. There will also be new rhythms and routines that arise — but they will be different and will take a long time to materialize.

And we aren’t done with the pandemic yet. We aren’t even halfway through. On July 1, the U.S. reported more than 50,600 cases in a single day, shattering previous records.

Nor is it just an increase in testing volume: The ratio of positive to non-positive test results is rising, even as ICU beds trend toward full or near-full capacity in multiple states.

If you drop an object of sizable mass from a far enough height, it will almost certainly deliver an impressive bounce.

And yet — as with a record jobs gain beset with asterisks in the middle of a pandemic — the bounce doesn’t have to be bullish.