Why the Coming Inflationary Era Could Kill off Passive Investing

Investors, on the whole, seem convinced that inflation will stay low; that interest rates can’t rise very much; and that passive investing is here to stay.

All three of those beliefs could be wrong, and the second two statements hinge on the first one.

If inflation comes back in a meaningful way, interest rates could rise again.

And both of those developments were structural — meaning inflation persists for a decade or more, and interest rates rise for that period — the passive investing model could be killed off.

Buying an index fund, and holding it, could then become a memory of times past.

On a global basis, accounting consultancy PwC sees passive strategies managing $36.6 trillion by 2025. If the forecast we see takes hold, that could melt away to nothing by 2030.

To see why this is not only possible, but likely, we first have to understand why inflation could return; and then second, we have to understand how inflation can utterly destroy passive investment returns.

For most investors, the possibility of inflation is hard to fathom today.

This is partly because so few remember what the last inflation-driven era was like, and partly because U.S. fiscal policy (government spending) has been relatively constrained for the past 20 years.

Over the past 20 years or so, the U.S. government has expanded the deficit for wars and tax cuts, but not for much else in comparison to decades past.

At the same time, foreign investment flows have readily funded the U.S. deficit, even as monetary policy — not fiscal policy — did the heavy lifting in terms of stimulating the economy (by driving rates to zero).

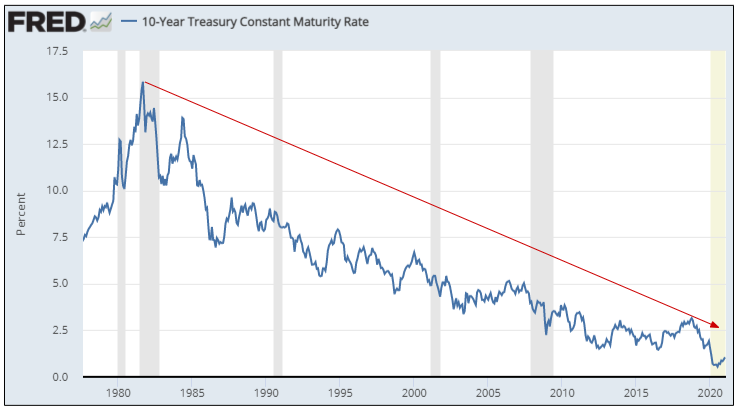

That is a unique set of circumstances that is now going away. We are heading into a new paradigm, though most investors don’t understand what that means. It is hard to grasp the magnitude of cyclical change when a multi-decade cycle, like the long-term debt cycle, finally starts to shift. The graphic below, via the St. Louis Federal Reserve, shows the interest rate yield on the U.S. Treasury 10-year note over the past 40 years, from 1980-2020. As you can see, yields have been falling (which inversely means treasury bond prices have been rising) nearly the entire time

The peak of the 10-year treasury yield, in September 1981, roughly coincided with peak inflation fear in the United States. Toward the end of the 1970s, American investors believed inflation was relentless and unstoppable and that inflationary conditions would last forever.

That belief was not only wrong, it was the capstone to an entire inflationary era.

Just as U.S. citizens reached their maximum level of conviction that inflation would never go away, a 40-year era of disinflation, and falling interest rates coupled with rising asset prices, was starting.

Four decades later, in 2021, American investors believe the opposite thing. They think inflation has been forever vanquished; that it can’t come back; that disinflationary pressures like aging demographics and deflationary aspects of technology will keep inflation at bay, and interest rates low, for decades more.

Investors are likely wrong on this point, too. We are witnessing the conditions in which a new inflationary era is being born.

And in that era, holding a passive stock index will be a nightmare, and holding a 60/40 portfolio might be even worse. These are strategies for a disinflationary era, in which interest rates are falling and general inflation is low. When the paradigm shifts in a meaningful way, these strategies could die.

What could make inflation return with a vengeance? There are multiple factors in play. But the single largest one is probably a whole new era of government spending.

People have pointed out, rightly, that the aging demographic of the Western world is deflationary. As baby boomers head into retirement, they spend less. Their consumption footprint shrinks. Those who head into retirement with no real savings see their lifestyles constrained even more.

The impact of rapidly advancing technology is also deflationary. Technology improves productivity by removing inefficiencies. The challenge is that one man’s inefficiency is another man’s gainful employment. Think what happens when millions of truck drivers are no longer needed; millions of fast-food workers; millions of dock workers; millions of radiologists, paralegals, and so on.

And yet, it is very important to understand something. As technology creates societal dislocations through massive job loss, governments will spend money to smooth over the cracks in a fraying societal structure.

And in order to ensure the job is done right, the government’s policy reaction function will be super-sized. They will spend more and more to keep democracy from breaking. And people will vote for this.

We are already seeing this happen. The future is now. In 2020, we saw a $2.2 trillion CARES act package, followed by a $900 billion add-on. Now there is $1.9 trillion worth of additional stimulus in the works, and a multi-trillion infrastructure package coming after that.

This is only the beginning, because the people like government money. And Republican voters like government money just as much as Democrat voters do.

“72% of respondents who voted for Trump believe that the stimulus checks should be greater than $600,” wrote Business Insider in December.

Fiscal help is not a partisan issue at the grassroots level. Americans want it. And as the job-erasing impact of technology disruption grows more intense — and as half or more baby boomers enter their retirement years dead broke — the demand for more fiscal stimulus, if not a kind of permanent stimulus, like universal basic income (UBI) through a back-door channel, will intensify.

And the government will be ready to provide. Janet Yellen, now confirmed as U.S. Treasury Secretary, recently wrote the following in a memo to 84,000 U.S. Treasury employees:

“Economics isn’t just something you find in a textbook. Economic policy can be a potent tool to improve society. We can, and should, use it to address inequality, racism and climate change.”

Translation: Do you like fiscal tsunamis? Because we’re ready to make them a thing.

Some argue that governments can’t create inflation. This is nonsense.

It is true that the Federal Reserve, on its own, cannot create inflation. The Fed is not allowed to spend money, or to send funds directly to households and businesses. It can only move interest rates around, or swap out dollars for treasuries or vice versa. (The U.S. dollar is just another government security, with a duration of zero years.)

But the U.S. government is allowed to spend money, and to “helicopter drop” large amounts of currency directly into the laps of people, businesses, and state municipalities.

Thanks to the power of the purse — and a sovereign government’s ability to borrow in its own currency — Janet Yellen can fulfill her aims. A government’s ability to create inflation is only a matter of political will.

If you think about it for a moment, this has to be true, because otherwise the government could print an infinite amount of currency, and distribute it in the most aggressive way possible, with no inflationary impact. That doesn’t make sense.

So inflation will be coming in part because we are in a new era of fiscal dominance — a period where government spending matters far, far more than the actions of the Federal Reserve, and where the job of the central bank is to clean up the mess created by wave after wave of politically popular fiscal initiatives.

In this new era, those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder will have new spending power via direct payments. In terms of inflation-generative activity, that is even more powerful than raising people’s wages. (Though wage hikes are in the works too, with the $15 minimum also a bipartisan popular issue.)

In a weird way, the deflationary impacts of demographics and technology will lead directly to inflation, by triggering the much larger, and more powerful, policy reaction impulse in the form of normalized fiscal spending. Call it killing the fly with a sledge hammer, or maybe a neutron bomb.

Then, too, we know that global central banks hold far too many U.S. dollars in their currency reserves mix — instead of 60% it should be more like 30 to 40% — and that a “global rebalancing” will mean a steady erosion in the value of the U.S. dollar. This will add to inflation pressures even more.

The story then gets worse, because the Federal Reserve will eventually have to implement something called “yield curve control” to support the tanking bond market. What this means in practice is that, as selling pressure on the bond market increases, the Fed will be the buyer of last resort.

But in order to buy up the excess supply of treasuries being sold, the Fed will have to pay with dollars. This will be the de facto “debt monetization” of the U.S. national debt, in which treasuries are converted to dollars, at a rapid clip, in real time.

This, too, will contribute to inflation, as will rising demand for grains, base metals, and fossil fuels in a world where supply shortages are structural (due to underinvestment in production capacity that cannot be corrected quickly). That means more inflationary pressure.

And then, last but not least, U.S. consumers will see, and feel, all of this inflation, and develop an inflationary mindset alongside the spending power provided to them by a generous U.S. government. This will spin the inflation flywheel even faster.

The net result of this could be a nightmare for passive investment strategies.

The chief problem for passive investing is that, in a truly inflationary era — unlike the four-decade “lowflation” era coming to a close — it is possible to lose money in a stock index, even if the price of the index goes up.

Think what happens if, say, the S&P 500 gains 4% in a year where inflation was 6%. The 6% loss to inflation not only cancels out the 4% gain, it leaves the investor 2% behind on balance.

If this happens for years on end — inflation outpacing the rate of nominal index gain — then holding a stock index will feel like a “mug’s game.”

History shows us how this works.

- Between January 1966 and December 1982, the S&P 500 index saw a nominal gain — in closing price terms — of 19.6%.

- But according to research analyst Jim Bianco, the S&P 500 lost 65% of its real value between 1966 and 1982 — nearly two-thirds — as a result of persistent inflation.

- Bianco further notes that, for an investor who bought the S&P 500 in 1966, it would not have been until 1993 — 27 years later — that the holding would have delivered real, inflation-adjusted gains.

The gist is that, in a time of structural inflation, a stock index doesn’t even have to go down for passive investors to lose money. It can go sideways, or creep higher in a lackluster way, and passive holders can still lose a bundle. All the index has to do is fail to keep pace with inflation, year after year, for passive investors to see the purchasing power of their savings eaten away.

This helps explain, by the way, why the stock market doesn’t have to decline in order to correct for too-high valuations. Failing to keep pace with inflation is a form of correction in itself, as real gains are eroded via nominal gains being worth less.

Another aspect of inflationary eras is that U.S. treasuries cease to be desirable assets.

When inflation is the order of the day, interest rates are rising over an extended period of time, which means bond prices are falling.

For investors in stocks and bonds — and particularly those in 60/40 portfolios — this creates the horrifying experience of seeing their stocks and their bonds decline in price simultaneously.

Once again, that is a different deal than what investors have grown used to these past 40 years.

Between 1980 and 2020, owning a mix of stocks and bonds in the same portfolio made sense because, when the stocks were going down, the bonds were probably rising — and if the Fed cut interest rates to stimulate the economy because stocks were down, the bonds would rise even more.

That whole rationale is why the 60/40 portfolio exists. But the structure depends on a disinflationary environment — an era where inflation is low or falling, which is the thing that makes bonds attractive.

When inflation is high or rising, the mix ceases to work, and the bond side actually becomes a liability (no more protection, and not enough yield, but plenty of risk).

This furthermore has big implications for “target date” funds, popular passive retirement vehicles that automatically allocate to a preset stock-and-bond mix.

When inflation truly returns, trillions of dollars in target date funds could be jettisoned. And investors everywhere will be asking themselves, why own index funds at all, just to get ravaged by inflation like this?

When you really boil it down, passive investing strategies were a kind of free lunch that persisted for decades. Passive methodologies were a simple, low-cost way to take advantage of falling interest rates and falling inflation levels, even as the U.S. economy expanded, central banks stayed accommodative, and government spending was constrained (at least in comparison to the 1930-1980 period).

All of that is likely going away, which means the low-effort returns of passive investing go away, too. Inflation eats them up, leaving the inflation-era investor worse off than before.

So is there a solution to this problem? Is there a way for investors to make money, and successfully fund their retirements, even in an inflationary era?

Yes, certainly. But the answer is old-fashioned: Investors will have to get involved with individual stocks and industries, and actively manage their portfolios again.

If they don’t, the only alternative will be to eat inflation losses. Such losses will be inflicted even if investors sit in cash (as cash will lose value too, through eroded purchasing power, over a long stretch of inflation years).

At the same time, opportunities will exist to beat the inflation bogey — and in many cases not only beat it, but crush it — by being invested in the right places, with the right levels of concentration.

The sickness that will infect stock indexes in aggregate will not impact the entire market. There will still be pockets of investment opportunity that do incredibly well, just as there were in the 1930s, and again in the 1960s and 1970s (the last time inflation had a heyday).

For those who are willing to be active, and who are willing to make concentrated investments while managing their risk, the shift to an inflationary era could well prove exciting and lucrative. For anyone inclined to be passive, however, there won’t be anywhere to hide.