Crude Has Some Good Years Left (the Oil Age isn’t Over Yet)

“The stone age did not end because the world ran out of stones, and the oil age will not end because we run out of oil.”

The Economist attributed that pithy statement to Don Huberts, the head of Shell Hydrogen, in 1999.

According to New York Times columnist Tom Friedman, it was first said by Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani, Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Oil and Mineral Resources from 1962 to 1986, as far back as the 1970s.

Either way, this notion of the oil age ending — for reasons other than depleted oil supply — has been around a long time. The thought is either 20-plus years old or 40-plus years old, depending on the source.

In the 1999 Economist piece, Huberts seemed to believe oil’s demise was imminent.

“The moment when an experimental technology becomes a commercial one is hard to define,” The Economist wrote, “but the new interest of oil companies, car makers, and power-engineering firms — almost all the industries that have a stake in the business, in fact — is a sign that fuel cells are crossing the line. Now that the energy business thinks that fuel cells are coming, they probably will.”

Twenty-two years later, we are almost there — or at least getting closer.

Today more than ever, there is reason to see the oil age is drawing to a close. From governments and the private sector alike, the signaling is hard to miss:

- More than a dozen countries and 12 U.S. states — including China, Germany, the United Kingdom, California, and others — have announced plans to either ban the sale of new internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles or require a switch to 100% zero-emission new vehicle sales over the next two decades, with the bulk of deadlines in the 2030-2035 range.

- The U.S. government has mandated all U.S. government vehicles to be zero-emission by 2030; China maintains its lead as the biggest electric vehicle (EV) market in the world through licensing fees and subsidies that overwhelmingly favor electric vehicles over diesel or gas-powered cars.

- General Motors — one of the largest automakers in the world, with annual vehicle sales in the seven to 10 million range — has pledged to invest $27 billion in EV research and production by 2025 and to phase out ICE production completely, going all electric, by 2035.

- Jaguar Land Rover, the luxury automaker with British roots now owned by Tata Motors, announced its Jaguar brand will be entirely electric by 2025; the entire Jaguar Land Rover line-up is slated to have e-models by 2030.

- Bentley Motors, the iconic luxury automaker owned by Volkswagen, announced all Bentleys will be electric by 2030.

- The euphoric stock market bubble that began inflating in 2020 — and easily qualifies as one of the grandest bubbles of all time — was largely centered around the EV space. While valuations in the EV space are beyond insane by rational standards — and will wind up crashing — the euphoria itself is a marker of the transformational impact EV will have. (World-changing technology revolutions have a longstanding habit of funding themselves through bubbles.)

- Climate change mitigation efforts and green energy initiatives are politically popular with the Millennial generation — which is far larger than the Baby Boomer generation — and efforts to go green are dovetailing with post-pandemic hunger for large-scale, FDR-style spending projects.

Natural gas could stick around because there are ways to make gas a zero-emission energy source; one can create “blue hydrogen,” for example, by using natural gas in the electrolysis process and capturing emissions for carbon sequestration.

For crude oil, though — long considered the world’s most important commodity — it truly looks like the days are numbered. The old saying was on point: The oil age will end with plenty of oil still in the ground.

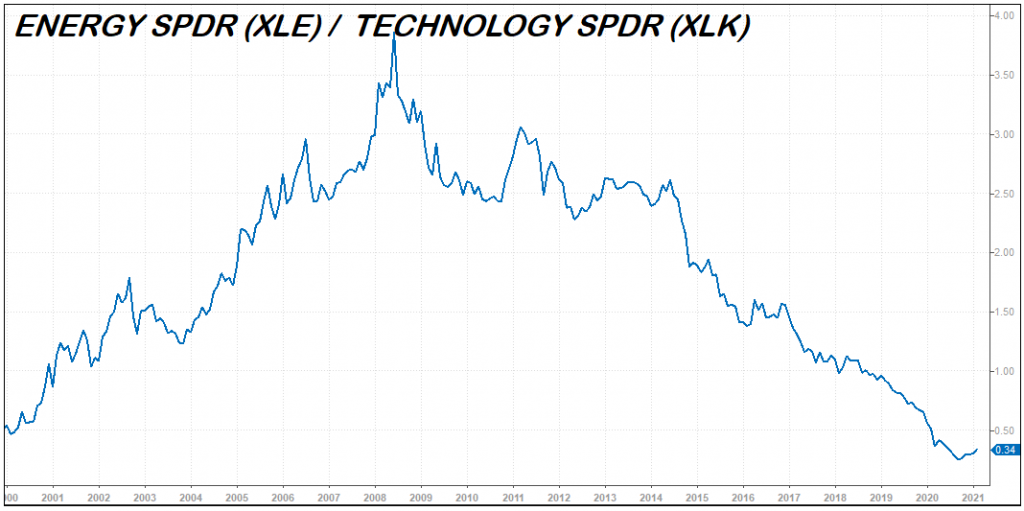

Oil will stay unextracted, in part, because investors are sick of throwing money at the process. Investing in fossil-fuel related businesses has mostly been an awful experience for the past 12 years; you can see this in the chart below, which shows the spread between the SPDR energy ETF (XLE) and the SPDR technology ETF (XLK).

In July 2008, the value of fossil-fuel related energy stocks relative to tech stocks peaked with the West Texas Intermediate crude oil price above $140 per barrel; from that point onward, old school energy versus tech has been downhill ever since.

The beaten-down state of the energy sector reflects a lack of willingness to put money into new oil projects. What is the point when crude oil demand will soon enough be going away?

Crude oil production, like most forms of commodity production, is a long-range affair when it comes to upfront investment cost. New crude oil projects require cash flow trajectory estimates over a period of several years, if not a decade or longer.

As a result of this, nobody wants to invest in long-range exploration or production for large-scale crude oil projects anymore. There isn’t much point when a giant “demand cliff” for oil is coming — the severe drop-off in crude oil demand that will come on a schedule as a result of government mandates shifting away from ICE vehicles and automaker plans to go full EV.

And yet, here and now in 2021, we would much rather invest in fossil-fuel related energy stocks than technology stocks. If you had to go long one and short the other, long oil stocks and short tech stocks would be the easy play.

Why are energy stocks a far more favorable play than technology stocks right now?

In part because energy stocks are still beaten down, as the XLE/XLK spread chart shows, whereas tech stocks have nosebleed valuations that are highly vulnerable to rising interest rates at the long end of the curve; and in part because a long-range, zero-investment outlook for oil is bullish in the medium term.

As the world prepares for a transition to electric vehicles, the paradox is that global oil demand will yet remain strong for years to come.

To put it another way, the EV hand-off will take a while; as a result, the world will need plenty of crude oil, not just for the next few years but likely until 2030 at least.

This telegraphed transition window creates a paradox. Oil demand is likely to remain strong for the foreseeable future, and yet investors will have little to no appetite for funding new oil projects (because of the demand cliff they can see in the distance).

That juxtaposition makes the medium-term oil outlook bullish, not bearish, because the global oil supply will start to feel constraints (due to lack of new investment) well before the demand picture tails off.

Then, too, climate change initiatives and government regulations meant to protect the environment are paradoxically bullish for oil prices, not bearish, to the extent they reduce the availability of new oil and gas supply and limit the reach of low-cost expansion.

When the Biden administration restricts oil and gas exploration on federal land, for example, they are helping the oil price more than hurting it by artificially constraining new supply; the same goes for stepped-up environmental regulations that shift marginal oil projects from viable to non-viable.

As strange as it may sound, we could even see oil prices above $100 per barrel at some point in the coming years. To see how, just picture a Middle East geopolitical flare-up; in the midst of a fiat currency crisis; after an extended run of global demand growth; with the humbled oil majors long having knocked their new production budgets down to zero.

Even as we finish this note, West Texas Intermediate crude is trading above $61 per barrel, with the global Brent crude benchmark above $63.

For the last decade or so, being bearish on beaten-down energy stocks, and bullish on world-beating tech stocks, has been a “no brainer” type stance; our hunch is that, for multiple sustained periods between now and 2030, the opposite will make sense.