The Great American Labor Strike?

Aislinn Potts is a 23-year-old aspiring writer and artist based in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. I’d never heard of her until yesterday.

I doubt you had either.

She’s likely never sold a book or painting before. But Aislinn generated one of the most widely read quotes of this week.

She had worked as an “aquatic specialist” – a fancy name for a retail position – at a national pet store chain. She quit that job in April. The job paid $11 per hour.

“It was a dismal time, and it made me realize this isn’t worth it,” she recently told The Washington Post. “My life isn’t worth a dead-end job.”

Potts isn’t alone in that sentiment. We’re witnessing more and more Americans channel their inner David Allen Coe, telling their bosses to “Take this Job, and Shove It,” as the country singer’s song goes.

In April, roughly 649,000 people in the retail sector quit their job.

That’s the largest single-month departure of Americans from retail jobs since the U.S. government started tracking worker movement more than two decades ago.

According to the Labor Department, 3% of the U.S. workforce – or about 4 million workers – put in their “two-week” notice and left their job in April 2021.

Employers reported 9.3 million open jobs in early June, a record for the U.S. economy.

What’s happening with the labor force requires more profound reflection.

The so-called labor shortage will significantly impact retail and hospitality companies that most analysts expected to rebound from the COVID-19 crisis.

Help Wanted!

The Pratt Street Ale House is a small restaurant in Baltimore, Maryland.

It sits about one-quarter mile away from Oriole Park at Camden Yards, home of the city’s Major League Baseball team. It hasn’t been crowded in the area for more than a year, but people are slowly returning to games and nightlife. When you walk in the door, a poster catches your eye.

“We’re Hiring. Starting Bonus Up to $400.”

The restaurant is offering to pay new workers $100 for every month they stay on the job.

Naturally, they had to stretch it over 120 days because they’d have incentivized everyone to quit if they received the bonus after 30 days.

I don’t know about you, but I see signs like this everywhere.

They’re in grocery stores, which – alone – lost 49,000 employees in April.

I’ve seen them on the streets beside nursing homes, which lost 20,000 employees across the nation in April.

You can find these signs at your local wine shop, the bookstore, and every restaurant on the block. I’ll bet that you won’t be able to unsee “Help Wanted” signs now.

Heck, in an economy facing shortages of everything, there could eventually be a shortage of “Help Wanted” signs because they’ve all been purchased and placed in windows.

But let’s take a step back: Why have companies in retail and services – the backbones of the U.S. labor force – faced tough challenges in finding workers?

Initially, the pandemic knocked out stores, restaurants, and related businesses for months. In addition, workers faced steep challenges in finding reliable transportation to work, child care, and reasonable hours as businesses cut back shifts.

But now, the other shoe has dropped.

Is This a Renaissance or a Strike?

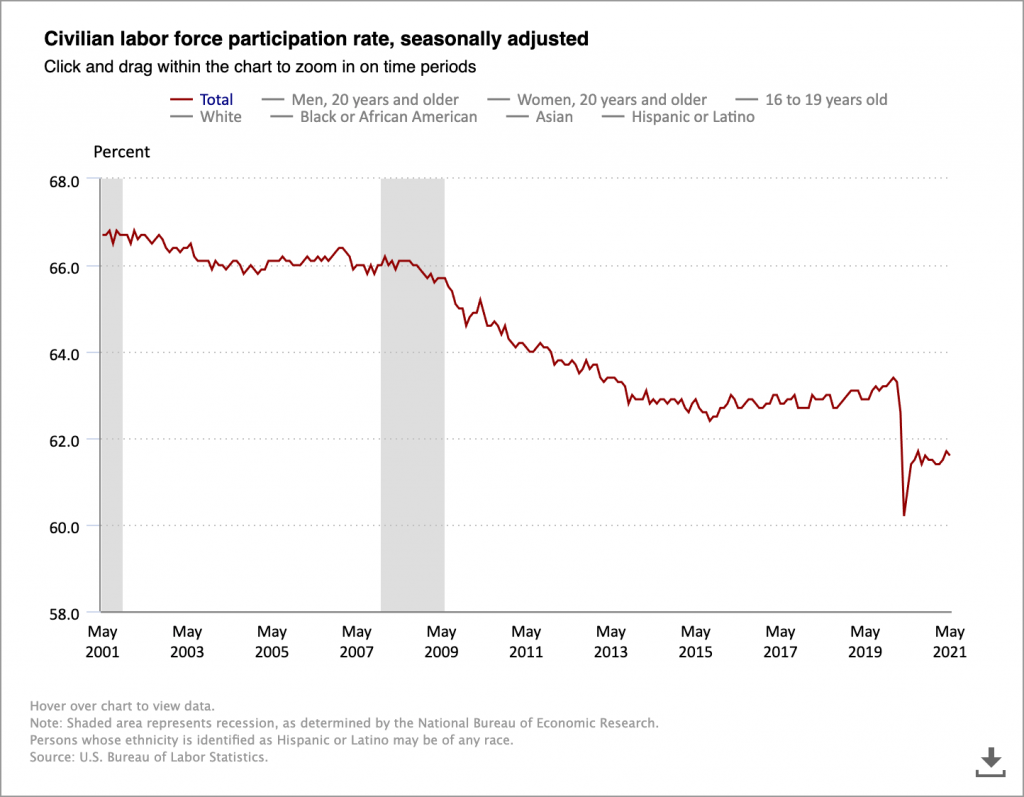

The United States has effectively wiped out a decade of labor gains in just the last year. If you look at the graph below from the U.S. Department of Labor , you can see that the workforce participation level has again dropped significantly.

In May of this year, 61.6% of the American labor force was employed. And labor force participation had been in a downward decline for the last two decades.

It has not recovered to pre-pandemic levels, and it looks like it could be a long time before we ever get back to where we were before the 2008 crisis.

Oxford Economics has argued there are four reasons why so many workers sit on the sideline. But, unfortunately, these are listed in no particular order or weight of Americans’ decisions to avoid work.

1. Would-be employees are still afraid of contracting COVID-19.

2. Federal jobless benefits that many argue incentivize people to stay at home instead of working.

3. Child care costs and obligations are keeping people at home (schools remain closed).

4. Many Americans are deciding to retire earlier than they had previously expected.

The second factor – jobless benefits – have generated the most controversy. Today, 25 Republican-run states have now reduced benefits to incentivize people to return to work. However, Americans aren’t just trying to get any job available for the sake of securing a paycheck.

According to a recent study by Yale economists, researchers found “no evidence that high UI [unemployment insurance] replacement rates drove job losses or slowed rehiring.” Similar studies from the Senate Joint Economic Committee and the University of Massachusetts revealed similar findings.

Something significant has changed.

Getting a job after the pandemic doesn’t appear to be just “about the money” or higher paychecks.

When members of the Federal Reserve warned that the recent jobs report might look a little weird, they weren’t considering a potential element that has shifted the perception of work in America.

The lack of a rush back to jobs might be about something else not considered by Oxford Economics.

Many U.S. workers also appear to want something better than the job they currently have.

Dr. Nancy Brune is the executive director of the Kenny Guinn Center for Policy Priorities in Nevada.

Last week, she argued that labor shortages are tied more to job satisfaction. As a result, many U.S. employees are choosing a new path in the post-pandemic economy, or they’re just staying home.

This is a very significant economic development. Once U.S. companies shifted manufacturing overseas, more American workers turned to the retail, restaurant, hospitality, and other service industry as a means of financial support.

But after decades of stagnating wages and uncertain futures, more Americans are looking for a different career path. A recent Pew Survey showed that 66% of unemployed Americans have “seriously considered” a career change.

Brune has called shifts in American job sentiment a “renaissance” and pointed to shifting trends in education, up-working, and new skills development.

If Brune is correct, we will experience a very rapid shift in reshaping the U.S. economy and its workforce. And even that reshaping faces obstacles.

For example, even if schools reopen in the fall (allowing employees to take a new job), keep in mind that we might have a shortage of child care workers and even teachers. It is a vicious cycle.

We could see a major impact on small businesses – already struggling from the pandemic as they struggle to attract or retain talent.

However, the companies that will survive already have strong balance sheets and enough cash on hand to weather this unpredicted storm. We’ll talk more about how to identify those potential winners soon. But, for now, pay very close attention to the shift in employment trends. This could be one of the most critical financial and social shifts for this economy in 40 years.