The Spectacular Twitter Hack is a Harbinger of Cyberwar

Twitter fell prey to a spectacular hack on Wednesday, July 15. It appears to be an “inside job,” with the hackers using a form of employee access to break into Twitter’s main database.

The hack was spectacular not due to the amount of money stolen — a little more than six figures as of this writing — but rather the celebrity nature of the accounts compromised.

The hackers sent out false tweets from, quite literally, some of the world’s most rich, famous, and powerful people.

The list includes four of the world’s richest men — Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Michael Bloomberg, and Elon Musk — along with former President Barack Obama and former Vice President Joe Biden — and the corporate accounts of Apple and Uber.

On top of that, they threw in Kanye West for good measure.

And yet, in comparison to the stunning sophistication of the hack, the method of monetization was amateurish and juvenile.

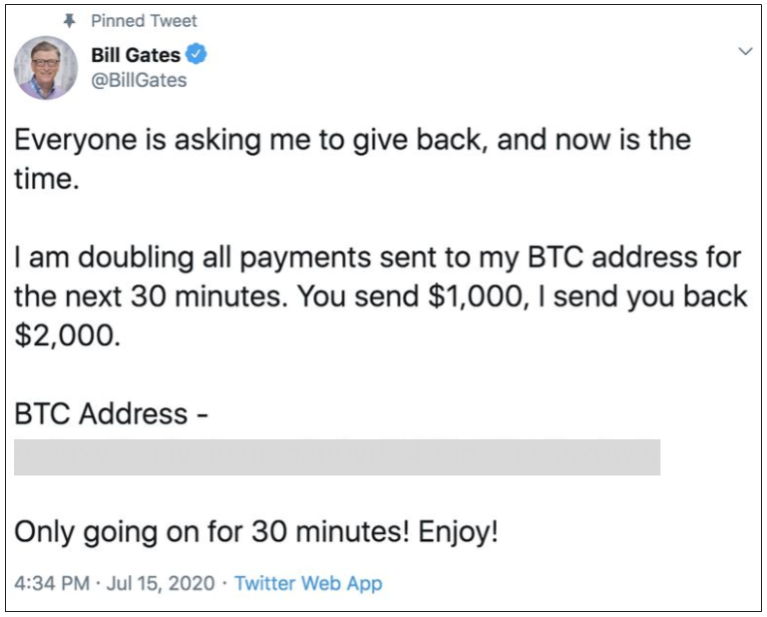

The hackers manipulated the list of targeted accounts to show a “Pinned Tweet” — a message that stays at the top of the page — in an effort to solicit Bitcoin in a non-reversible transaction. For most of the hacked accounts, the Pinned Tweet resembled the screenshot below.

The hackers encouraged crypto holders to send Bitcoin to the posted address (grayed out in the above example) as a form of non-reversible transaction.

According to analysis from Elliptic, a cryptocurrency compliance and research firm, the hackers received about $121,000 worth of Bitcoin spread out over 400 payments. The single largest payment, originating from a Japanese cryptocurrency exchange, was for $42,000.

Twitter is facing some hard questions as a result of the hack, though the stock price isn’t reflecting it. As of midday on July 16, TWTR shares were down less than 2% on the day.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the hack, as acknowledged by Twitter, is the “social engineering” component, in which the hackers got access to Twitter with the help of an employee.

“We detected what we believe to be a coordinated social engineering attack by people who successfully targeted some of our employees with access to internal systems and tools,” Twitter reported via Tweet.

The United States probably got lucky with this hack, which was uniquely high-profile, yet low damage (roughly 13 Bitcoin getting stolen).

Imagine what could have happened, though, if the hackers had gotten into the Twitter account of the President of the United States — and used their imagination to wreak havoc.

Or think what could happen if an important government agency, far more important than Twitter, was compromised in the same “social engineering” style as the prelude to an act of cyberwar.

The threat of cyberwar is real and serious. Some nations are already on high alert.

In June 2020, for example, the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison warned of “sophisticated state-based cyberattacks” deliberately targeting Australia.

Within two weeks of Morrison’s announcement, the Australian government had committed to recruiting 500 “cyberspies” to bolster counterattack capabilities, while allocating $1.35 billion Australian dollars (about $930 million U.S.) over a 10-year period for stepped-up cyber defense.

Nor is cyberwar a new thing. In April 2007, the country of Estonia was hit by a cyberattack orchestrated by the Russian government.

“Massive waves of spam were sent by botnets and huge amounts of automated online requests swamped servers,” according to the BBC. “The result for Estonian citizens was that cash machines and online banking services were sporadically out of action; government employees were unable to communicate with each other on email; and newspapers and broadcasters suddenly found they couldn’t deliver the news.”

The infiltration of Twitter is a stark reminder. A cyberattack of a far more serious nature could be unleashed on the United States — and even be a kick-off to cyberwar.

The more digitized the economy becomes, the more that critical physical infrastructure becomes exposed to hacks. For example, imagine if large portions of a city’s power grid were taken offline, or the air traffic control tower for a major airport was disabled.

It isn’t just Twitter, in other words, that should answer hard questions and substantially upgrade its internal security practices.

The United States government, too, should be taking a hard look at cybersecurity holes and digital vulnerability points — particularly with the 2020 election just months away. Otherwise, the next high-profile hack could be far more spectacular — and the costs far more dire.